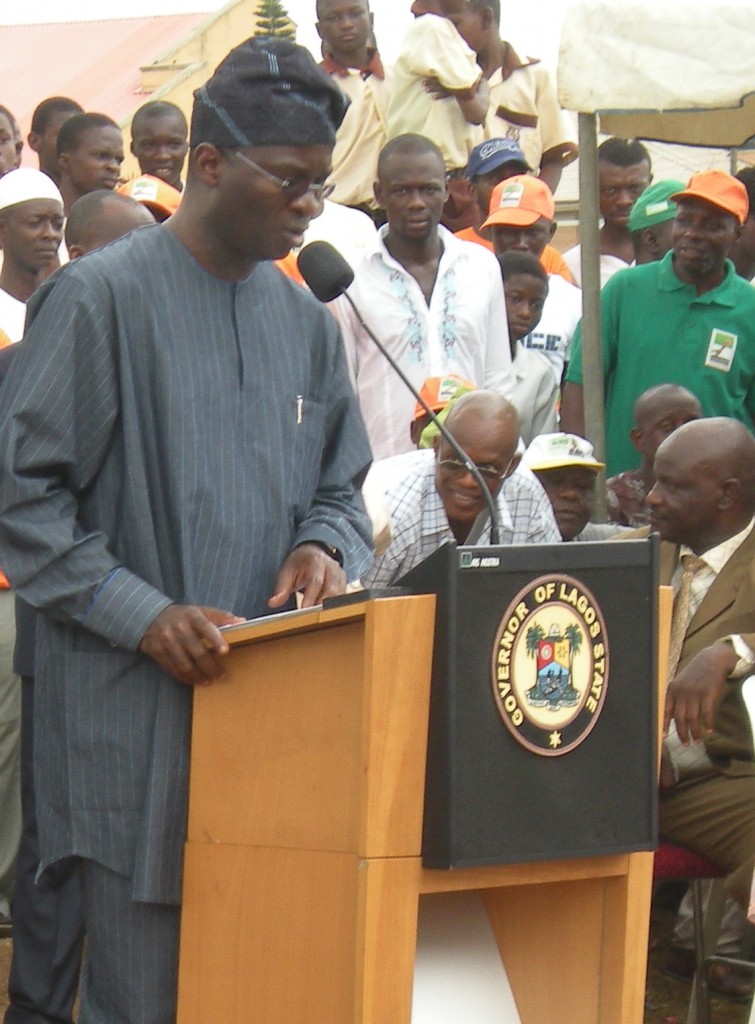

Babatunde Fashola, the governor of the state of Lagos, recently came to speak at the Rhode’s House in Oxford for the Oxford Research Network on Governance (you can watch or listen to that talk at the Democracy in Africa blog).

Fashola has been an intriguing figure for quite some time, being somewhat of an outlier in a country with an unfortunate reputation for poor governance and excessive corruption. His efforts to reform the city of Lagos were even praised earlier this year in The Economist, which is not itself known for overly-upbeat coverage of sub-Saharan Africa.

The first thing that jumps out when you listen to Fashola, both at the Rhode’s House talk and his `I See Lagos’ speech here, is his fixation on public goods – most often new types of transportation and infrastructure. This stems from exposure to reliable public services during his childhood – as a little boy, Fashola recalls taking a bus to school every day. He has laid out his vision for the city in recent campaining, and it looks very similar to the type of public transportation networks we’re used to in Europe – high speed rail, bus and ferry networks, all looking very clean and efficient.

This may all seem terribly optimistic, but it’s clear that Fashola’s zeal for public goods is paying off politically: despite some rumblings from the political elite, he was re-elected for a second term this May in a landslide victory – carrying over 80% of the vote.

Yet the governor’s support appears to extend further than just the poll booth: Some recent research by Nic Cheesman (a research affiliate of ours), Etannibi Alemika and Adrienne LeBas suggests that a majority of Lagosians are now willing to to be subject to taxation in exchange for competent government services.

Why is this important? Development wonks often talk about how a `social contract’ can be established around taxation. If a state wants to levy serious taxes, its population has a degree of bargaining power – if you are planning to take some of my money then you’d better do something useful with it – and so the state is forced to be more efficient.

This is why those same wonks get terribly nervous when a country discovers a resource (such as oil) which allows the government bypass this contract, thus allowing it to stay in power regardless of whether or not its citizens pay up. Perhaps it is then lucky that the state government of Lagos gets most of its revenue from taxation, making it significantly beholden to its citizens. The dependence is palpable – the government’s online information campaigns espouse the usefulness of this taxation in generating public services.

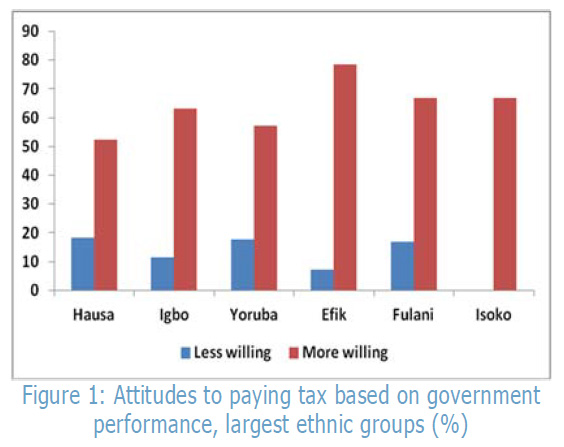

What’s particarily remarkable about the social contract that seems to be emerging in Lagos is the fact that it is cross-ethnic, another finding from Nic’s research: willingness-to-pay for public goods doesn’t seem to vary greatly across ethnic groups.

Societies marked by deep ethnic cleavages are typically characterised by low levels of trust and public goods provision, often because government resources are directed towards private patronage instead of building roads. This can feed back into the willingness to be taxed, as the population is hesitant to spend money that will just end up in the pockets of other ethnic groups. Perhaps by making a credible commitment that the state government isn’t going to divert resources, Fashola has broken this unfortunate cycle.

Not all is perfect though – while the Governor appears keen to create a safe, secure, pro-business environment in Lagos, crime and harassment from the police still represents a large burden on potential entrepreneurs. The same survey by Alemika, Cheesman and LeBas revealed that the average Lagosian trusts a stranger more than a police officer, and that those who mistrusted the police were more likely to have been victims of crime. Furthermore, respondents who had negative experiences with crime or distrusted the police were less likely to invest in starting a new business. While it’s difficult to disentangle the direction of causality here, it’s obvious that Lagos still has a long, long way to go before it converges with the more peaceful setting of Fashola’s youth.

- Nic Cheesman’s Democracy in Africa blog has some more details on the Fashola talk here.

- iiG has put together two briefing papers with more details on the results from the Lagos surveys here and here.