In every society, the correct functioning of economic, political and social institutions relies on the establishment and enforcement of norms guiding the behavior of the members of that society. In recent years there has been increasing interest in both the design and implementation of mechanisms for enforcing these norms, relying on social judgement and informal fines and/or rewards. Social enforcement mechanisms seem especially important in countries characterized by poor formal institutions, where, due to limited resources and pervasive corruption, top-down enforcement mechanisms are likely to be ineffective.

One example of an enforcement mechanism which has been gaining in popularity is the “I paid a bribe” website, first launched in India and subsequently replicated in Kenya, Indonesia, Zimbabwe and Pakistan (http://www.ipaidabribe.com ). The website gives citizens the opportunity to anonymously report their bribery experiences, hence increasing the observability of acts of corruption on the part of public officials and civil servants. Although the I Paid a Bribe websites are highly used, their effectiveness in the reduction of corruption has yet to be scientifically tested.

However other types of social enforcement mechanisms are beginning to be tested: a number of empirical evaluations aimed at limiting violations of societal norms such as corruption, absenteeism and poor performance of service providers have been recently conducted in developing countries. The results are mixed, ranging from successes in the monitoring of teacher attendance in Kenyan and Indonesian schools, and of health professionals in Uganda, to the failures of similar mechanisms in the context of Indian schools, and Indonesian road construction programs.

While enforcement mechanisms relying on social observability and informal sanctions seem to be, at least theoretically, a viable solution to the deficiencies of top-down systems, their effectiveness depends crucially on i) on how society views the violation of a given norm, ii) how willing individuals are to socially punish those that violate the rules, and iii) how responsive those that break the rules are to these `social sanctions’.

Indeed, societies greatly differ in both the degree of importance given to different rule-breaking behaviors and the severity with which violation of the rules are judged. In some societies it may be the case that petty crimes – such as cutting the line in a public office or at a bus stop – may not be viewed harshly or subject to much disapproval, whereas in other contexts these might be seen as more serious infractions, warranting some sort of social sanction. Even more serious crimes (such as tax evasion and corruption) may be harshly condemned socially in one country while being widely accepted or even informally-rewarded in another. Therefore, it is possible that relying on social judgement and informal sanction-based enforcement mechanisms to thwart certain rule-breaking behaviors such as bribery and embezzlement of public resources might succeed in some environments, yet fail in others. Put differently, social norms and culture may play a significant role in determining the effectiveness of any given social enforcement mechanism.

In recent research with Tim Salmon, we asked whether pre-existing social norms and culture significantly affect the effectiveness of enforcement mechanisms which rely on social judgement and informal sanctions. To answer this question, we experimentally-investigated the extent to which the effectiveness of enforcement mechanisms is dependent on the cultural background of the potential rule breaker. Our approach was to take a sample of individuals from many different socio-cultural backgrounds, place them all in exactly the same formal institutional context, give them the chance to engage in different forms of rule breaking and then investigate how they responded to the same enforcement mechanism.

To this end, we conducted a specially-designed laboratory experiment with a sample of individuals who both grew up and currently live in the US, yet identified culturally with different countries, corresponding to the countries of origin of their ancestors (prior to migrating to the US). Given the immediate implications for designing social enforcement mechanisms in developing countries, we were especially interested in the role social judgement might have in deterring bad behaviour in individuals who identified culturally with countries with poor rule-of-law.

The experimental study

We conducted a laboratory experiment that simulated three rule-breaking situations: theft, bribery and embezzlement. Our experimental participants engaged in these rule-breaking games under three separate scenarios, each with a different degree of `social observability’ and the potential for others to express social disapproval. The first `treatment’ or situation was one in which the rule breaker’s actions were completely hidden from the victim. The second and third treatments allowed for, respectively, the victim to be informed of the rule breaking behavior and then finally for both the direct victim and players acting as “other members of society” to send social messages to the rule breakers. Our aim was to investigate whether individuals in the potential rule breaking role respond differently if they knew that their action would be hidden from others or if they knew that it would be visible to the victim and potentially judged by others. The social messages that victims and other members of society could choose to send to rule-breakers are displayed in Figure 1.

Our Cross-Cultural Sample

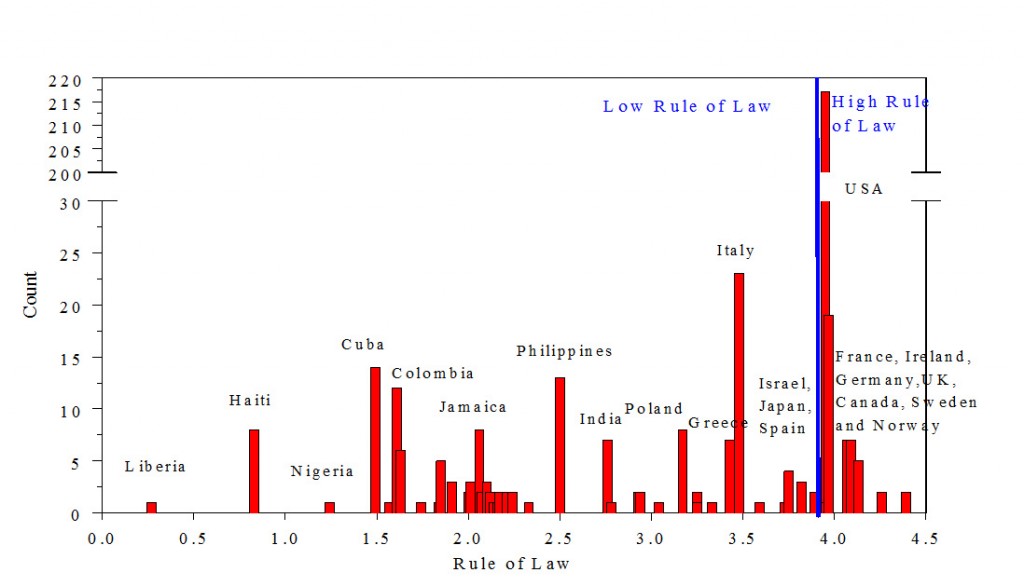

The study involved 432 student subjects enrolled in a large US state university. We captured differences in cultural heritages by asking participants whether they and their families identify culturally with a country other than or in addition to the USA. About 50% of the students answered positively. A total of 52 countries are represented in our sample, ranging from Low Rule of Law countries such as Liberia and Nigeria to High Rule of Law countries such as Sweden and Norway. Figure 2 shows the distribution of the countries of origin of our experimental participants ordered according to the World Bank’s Rule of Law governance indicator.

Results and Policy Implications

By combining our experimental and survey data, we were able to see whether individuals with different cultural backgrounds respond differently to increased observability of their actions and to the possibility of social judgement. Our results indicate that this is the case: in particular, while subjects that identify culturally with high rule of law countries responded to the possibility of social judgement by decreasing their rule-breaking behavior, those who identified with low rule of law countries did not.

Our findings suggest that, while development policies that rely purely on social judgement and informal sanctions to prevent rule breaking behavior may work with high rule of law populations, they may be less likely to work with populations accustomed to low-rule-of law contexts. A more general implication of these results is that when designing and implementing a social enforcement mechanism, one must give very careful thought to the specific populations being targeted by the mechanism and the cultural contexts in which they are embedded.