By Janina Steinert – University of Oxford.

Living in poverty is not only a shortfall of money but also a daily struggle for securing food and basic needs. The “one dollar a day” analogy is delusive in that the dollar is not available every single day. Saving and careful financial planning thus become essential tools for addressing income volatility and smoothing consumption over time. Accordingly, empirical evidence shows that the financial portfolios of the poor go beyond mere hand-to-mouth survival and unfold in complex systems of spending, saving, and borrowing (Collins et al. 2009).

Acknowledging the importance of healthy money management, previous interventions have focused on building financial literacy and promoting savings. Proponents have described these programmes as cost-effective and empowering (compared to cash transfer programmes) and as low-risk and sustainable (compared to microcredit programmes). Their prominence – both in development practice and research – is emphasised by 115 experimental and quasi-experimental impact evaluations of financial education programmes identified in a recent meta-analysis (Kaiser & Menkhoff 2016). However, synthesised evidence from this meta-analysis reveals that financial literacy programmes remain far less beneficial than they promise, and particularly so for low-income populations.

In our recent CSAE working paper we therefore set out to examine how the effectiveness of financial literacy programmes can be increased. For this, we draw on emerging evidence from a range of projects that integrate poverty alleviation strategies with psychosocial programme components. Examples are the Becoming a Man (BAM) programme for economically disadvantaged youth in Chicago that features both behavioural therapy and financial literacy training (Heller et al. 2017) or the Sustainable Transformation of Youth in Liberia (STYL) programme which offers behavioural therapy and unconditional cash grants (Blattman et al. 2017). Motivated by the success of these previous programmes, we test the effectiveness of a group-based parenting and financial literacy training for poor families in the Eastern Cape, South Africa’s most deprived province.

Our programme, named Sinovuyo Teen, is composed of 14 weekly sessions that are delivered by community social workers to small groups of around 15 adolescent-caregiver pairs. 12 of these sessions are built on evidence-based parenting principles, including modelling of positive behaviour, anger and stress management, promotion of praise and self-worth, as well as establishing rules and routines in a household. The economic part of the programme is covered in two sessions focused on budgeting and saving training as well as commitments for family saving goals.

Figure 1: Group session in treatment village (Source: Sinovuyo Teen Project)

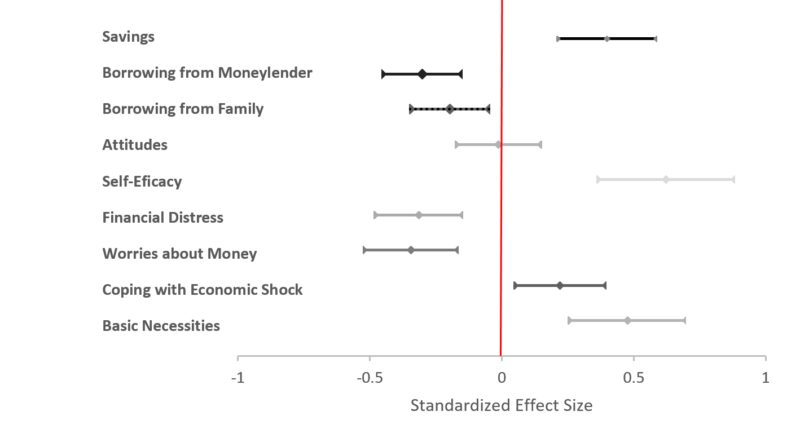

To evaluate the impact of the programme, we ran a field experiment with 552 families from 40 village clusters. 20 villages were randomly selected to receive the Sinovuyo Teen programme and the remaining 20 to receive a one-day hand washing intervention (serving as our control group). At 5-9 months post-intervention, we find that participants from the treatment group have significantly changed their financial behaviours: They save more and borrow less, particularly so from moneylenders. We also observe significant decreases in financial distress, improved resilience to income shocks, and better access to a range of basic necessities, including education, medical care, and clothing.

Figure 2. Standardised intent-to-treat effect sizes at post-test (adult report)

Our results compare favourably to previous financial literacy programmes. We draw on qualitative evidence from in-depth interviews with programme participants to understand how the programme’s success might be explained. The data reveals four possible channels of programme effects: First, budgeting and saving training has likely increased financial self-efficacy and consequently helped to materialise pre-existing saving intentions. Second, commitments to saving goals and adoption of new rules and routines have likely helped prioritise essential expenses over others and reduce impulsive decision making. Third, promotion of praise, positive communication, and self-esteem can counter procrastination and hopelessness and thus motivate future aspirations in terms of investments in education and family business. Fourth, endorsed financial behaviours have likely been reinforced through peer pressure both in group-based sessions and in participants’ homes.

Based on our findings we contend that “hybrid” programme curricula that embed financial literacy training into wider psychosocial interventions are likely more successful than stand-alone financial literacy training.

References

Blattman, C., Jamison, J. C., & Sheridan, M. (2017). Reducing Crime and Violence: Exper-imental Evidence from Cognitive Behavioral Therapy in Liberia. The American Econom-ic Review, 107(4), 1165–1206.

Collins, D., Morduch, J., Rutherford, S., & Ruthven, O. (2009). Portfolios of the poor: how the world’s poor live on $2 a day. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Heller, S. B., Shah, A. K., Guryan, J., Ludwig, J., Mullainathan, S., & Pollack, H. A. (2017). Thinking, Fast and Slow? Some Field Experiments to Reduce Crime and Dropout in Chi-cago. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 132(1), 1–54.

Kaiser, T. & Menkhoff, L. (2016). Does Financial Education Impact Financial Behavior, and if So, When? DIW Discussion Papers 1562.

Steinert, J.I., Cluver, L.D., Meinck, F., Doubt, J., Vollmer, S. (2017). Household Economic Strengthening through Saving and Budgeting: Evidence from a Field Experiment in South Africa. CSAE Working Paper WPS/2017-11.