Crossing a national border in East Africa can be a ponderous, aggravating affair. I experienced this firsthand a few years ago while attempting to temporarily bring a car into Tanzania from Malawi. The process took several hours and involved a never-ending amount of detailed paperwork on both sides of the border, as well as multiple and seemingly-illogical shifts back and forth between offices, a minor panic attack when the resident soldier inadvertently pointed his machine gun at me and finally a mad dash into an adjacent village to find someone who could photocopy our documents.

It’s easy to see how these sort of hurdles can disrupt markets, even without the distortions caused by formal tariffs or other restrictions on trade. This is of particular concern for countries in sub-Saharan Africa, many of which already face large transportation costs due to poor infrastructure. Landlocked countries are especially reliant on their neighbors for access to imports, so there is great interest in getting goods across borders as efficiently as possible. This motivates a search for finding good ways to measure the impact of international borders on market efficiency.

As much as they enjoy wallowing in theory, economists also like to learn from situations where theoretical predictions don’t hold. One of these `predictions’ which might be useful for examining border effects is the law of one price (LOP), the assertion that identical goods will always be sold for the same price within a market. The standard example is that if shop A on one side of town is selling bread for $0.80 a loaf and shop B on the other side is selling it for $1.00 a loaf, there is an arbitrage opportunity, with gains to be made from buying bread at $0.80 and selling it outside of shop B for $0.99. In an ideal setting this incentive to exploit differences in prices eventually drives those prices to equalize through competition.

Yet there are a lot of reasons why the LOP might not hold – one common one is the presence of transportation costs (in my example above the arbitrage opportunity vanishes if it costs me $0.25 to move a loaf of a bread between the shops). While the LOP is more of a theoretical ideal than an empirical reality, it is a reasonable benchmark for testing whether or not markets are working efficiently: if two identical goods are being sold for separate prices in otherwise identical settings, we know something is amiss. Looking at the prices of identical goods on either side of a border might tell us the extent to which borders are preventing prices from equalising.

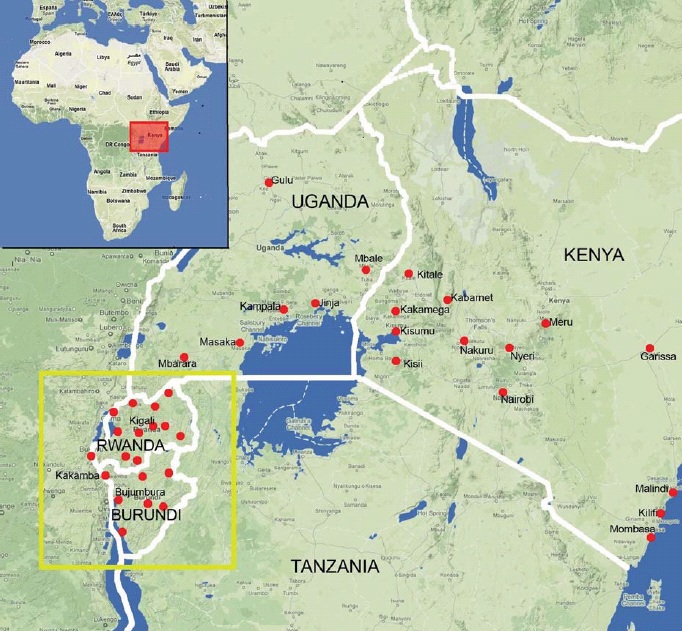

In a new working paper, Bruno Versailles uses monthly price data from cities in Uganda, Kenya, Rwanda and Burundi to do exactly this. To disentangle the effect of a border from that of distance, he compares prices between cities both within and across these countries, while also trying to account for other factors that might drive a wedge in prices, such as disruptive changes in the exchange rate or non-tariff barriers to trade (think number of offices one has to run between in order to get their car cleared).

Despite controlling for these potentially-confounding factors, borders still appear to impede market integration – price differences are significantly larger (between 13 and 20%) between cities if they fall on opposite sides of a border. These price effects are roughly comparable to those created by moving the two cities between 300 and 6,000 kilometers apart, depending on the specification.The effect is also additive – cities which are divided by two borders see a larger divergence in price than those with only one border in between them.

The implications of these results are especially insightful given the setting: together, these countries account for four out of the five member nations of the East Africa Community (EAC), all facing a future of increased economic integration and easing of border restrictions. The EAC introduced a customs union in 2005 aimed at zeroing all tariffs between member countries, establishing a common external tariff and attempting to reduce non-tariff barriers as much as possible. While Bruno does find that price differences between Kenyan and Ugandan cities (Rwanda and Burundi had yet to join) did fall every so slightly after the customs union was adopted, the border effect still persists, suggesting that integration still has a long way to go.

Still, despite the existence of border effects, distance between cities still appears to be one of the primary drivers of deviations from the LOP. The effects in this study are particularly large – two cities only 100km apart see a 13% increase in price differences. Even if EAC countries get their act together and further reduce border costs, there still needs to be more attention given to reducing transportation costs within countries, where poor roads and corruption remain a problem. A study by Rwanda’s Private Sector Federation found that the trek from Mombasa to Kigali required a whopping 36 stops and $864 in bribes, mostly at police checkpoints and weigh stations within countries, rather than at the border.