Commodity price shocks can have powerful but unequal effects on labour, capital and land. A large literature, often referred to as the ‘Dutch Disease’ literature, documents the effects of these commodity booms on factors of production. An increase in global demand for a commodity and its subsequent price will trigger a sharp rise in a country’s exports of that commodity. Typically, this causes an appreciation in the exporter’s real exchange rate, which in turn harms the competitiveness of other sectors which export, such as agriculture and manufacturing. Thus, resource booms caused by a rise in global demand might lead to a decline in employment in these sectors.

Even though the channels through which these commodity booms affect employment in resource-rich countries are well understood, surprisingly little is known about how the impact the distribution of income within these countries. Theoretically, the distributional impact of a commodity price shock should be modest if resources are mobile, as both people and capital can move across sectors to take advantage of increased prices. However, if there are constraints on mobility between sectors, then price shocks might have significant distributional consequences.

Furthermore, those who write about political economy theory often argue that natural resources could have a significant impact on income distribution via institutions (see Stanley Engerman and Kenneth Sokoloff’s book or work by Acemoglu and Robinson and Acemoglu et al.). They argue that natural resources influence the initial distribution of both wealth and income, and thus of economic power. This distribution of economic power determines, in turn, the shape of future institutions and policies. Therefore income and wealth inequality might persist over the very long run. However, the nature and magnitude of the impact of natural resources on income and wealth distribution might depend on the type of the natural resources, who owns them, and other factors determined at the start.

This ambiguity over what the impact of natural resource booms on income inequality makes this an ideal question to study empirically. In a recent CSAE working paper, I and Jeffrey Williamson address this question by studying the association between commodity prices and income distribution in Australia for a century.

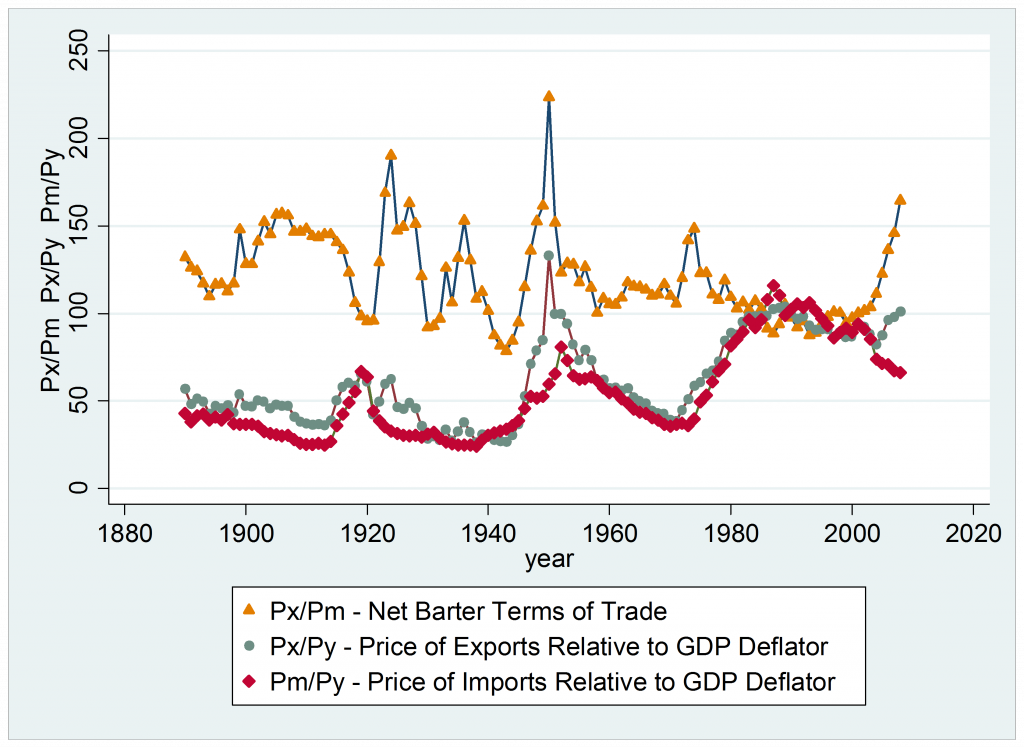

Figure 1: Australian terms of trade from 1890 to 2007

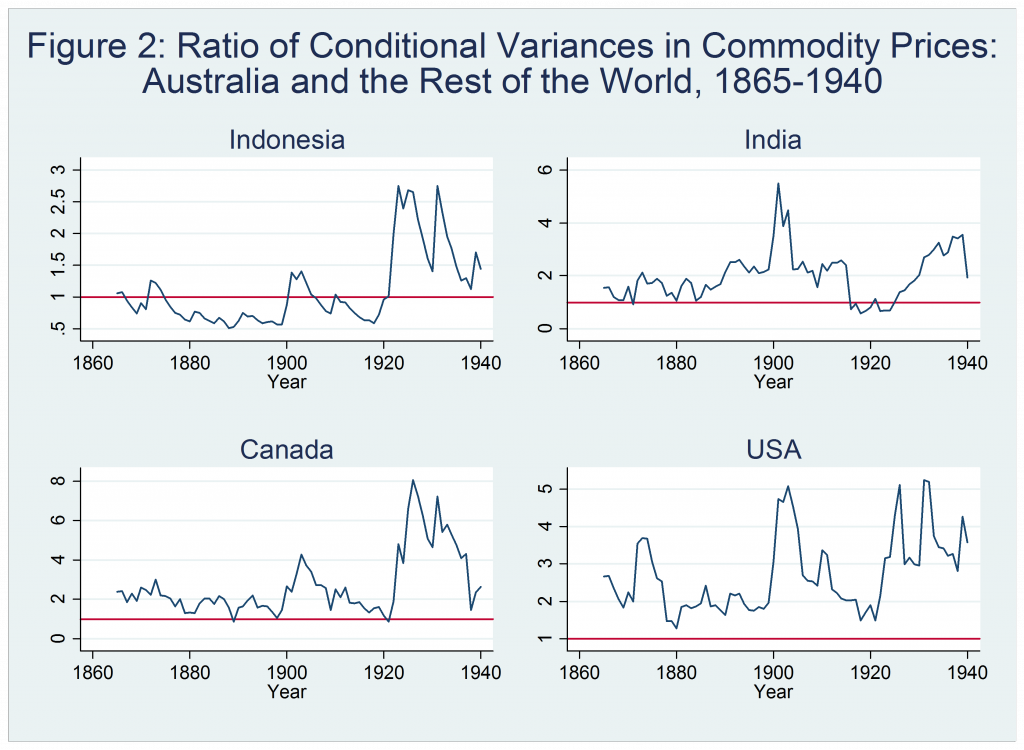

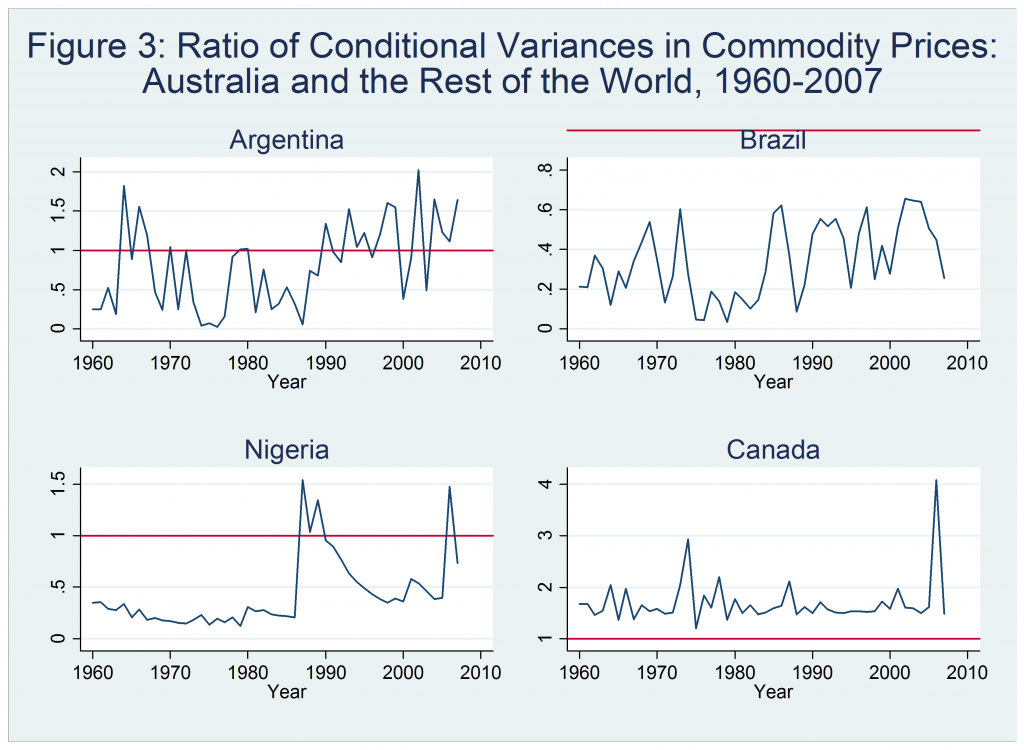

The key facts that we discover are as follows: first, Australia has undergone three major commodity price episodes over the past century. These can be seen in Figure 1, which shows how Australia’s terms of trade (the relative price of its exports over imports) and overall deflated price of exports and imports have changed over time. The first half of the 1920s experienced a sharp increase in Australian commodity prices. The second major price shock occurred during the Korean War episode from the late 1940s to the early-mid 1950s and the third has been occurring since 2003 (a detailed historical account of these shocks can be found here). First, in terms of magnitude, the Korean War boom was the most dramatic. Second, the size and frequency of commodity price shocks experienced by Australia over the periods 1865-1940 and 1960-2007 are large relative to many other commodity exporting countries: Figures 2 and 3 show how the fluctuations in Australia’s commodity prices during these periods compared to other countries.

Finally, we find that these commodity price shocks increased the share of income held by the top 1, 0.05 and 0.01% of Australians considerably both in the long and short run. This result held even after we accounted for a host of other factors such as GDP growth, wartime conditions, trade union density, direct tax shares in GDP, and enterprise wage bargaining. Out of these commodity shocks, both wool and mining prices, rather than other agricultural commodities, have been the main drivers of Australian inequality in the short run. However, in the long run, a sustained increase in the price of renewable resources, such as wool, reduced inequality whereas sustained increases in non-renewable resources, such as minerals, increased inequality.

What are the key lessons from this exercise? Our analysis shows that resource booms tend to exacerbate inequality. The recent literature on the economic consequences of inequality argues that high and persistent inequality not only harms growth but also adversely affects institutions (some examples here, here, here and here ). Therefore, it is important for resource-rich developing countries to use policy to tackle inequality that emerges as a consequence of commodity export booms.

Yet, it is not clear that these sorts of policies are as politically feasible as they might be in more mature economies like Australia. Thus, we hope that future research will utilise better data on price shocks and inequality from developing countries to see whether or not the impacts are larger than what we find in Australia, as the political economy literature would predict.

Nevertheless, our analysis here seems timely and relevant, not just for Australia, but for all resource-rich developing countries as the price volatility experienced by the former following the late 19th century was even greater than that for the average exporting low income country. Thus, studying the distributional impact of commodity price shocks in Australia could yield important lessons for resource-dependent countries in the developing world.