The economic losses due to mental health disorders in low-income countries are staggeringly large. Depression alone generates an estimated loss of 55.5 million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) in low- and middle-income countries. That number is less than a fifth as large—10 million DALYs—in high-income countries. Investment in prevention and treatment remains low, but developing country governments and aid organizations are beginning to turn their attention to mental health policy. For example, Ghana, where our study is based, passed a landmark Mental Health Act in 2012. It’s crucial, then, as the tide of policy begins to shift, to understand the origins of mental health disorders in low-income country contexts.

James Fenske, Anant Nyshadham, and I set out to do exactly that in a recent CSAE working paper titled “Early Life Circumstance and Mental Health in Ghana.” We study the relationship between early life conditions and adult psychological distress. Medical evidence suggests that some components of mental health are coded during fetal development. Changes to the fetal environment, if they alter or disrupt this coding process, may have long-lasting impacts on mental health. These “disruptions” may be particularly common in low-income populations, whose smoothing and coping mechanisms are limited.

The households we focus on are cocoa farmers. They, and millions like them across the developing world, are commodity suppliers to global markets. The wide and persistent price fluctuations that characterize these markets directly affect the livelihoods of smallholder suppliers, leaving households (and especially young children) vulnerable.

Cocoa is Ghana’s chief agricultural export commodity, and its price is a key determinant of farm households’ income in regions where it is produced. We show that in these regions, low cocoa prices at the time of birth substantially increase the incidence of severe psychological distress, as classified by the Kessler Scale, an internationally validated measure of anxiety-depression spectrum mental distress. We estimate large impacts of these price fluctuations. A one standard deviation drop in the cocoa price increases the probability of severe mental distress by 3 percentage points, or nearly 50 percent of mean severe distress incidence.

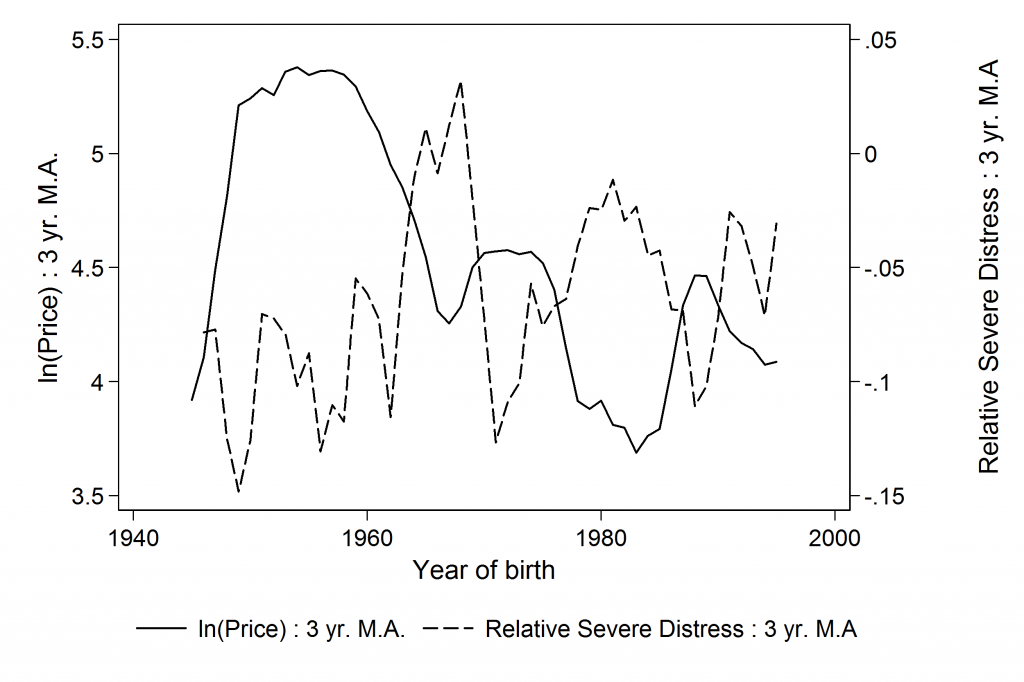

Perhaps the best way to summarize the relationship between prices in early life and adult mental distress is through the following figure. We graph real cocoa prices over the birth years of individuals in our data. On this time series, we superimpose the rate of severe mental distress for each birth year cohort in cocoa regions relative to the same rate for the same cohort in non-cocoa regions. This trend tells us the extent to which the relative rate of mental distress across these regions fluctuated over birth cohorts. There is a clear negative relationship between the two: when cocoa prices at birth are high, the relative rate of mental distress is low, and vice versa.

What drives the large and long-lasting impacts we uncover? We find evidence consistent with the hypotheses that maternal nutrition, reinforcing childhood investments, and adult circumstance are all operative channels of impact. We also take a careful look at selective fertility and mortality, both of which could explain some part of the mental health impact. Our results suggest that fertility does indeed respond to cocoa prices, but that selective fertility cannot account for the bulk of our estimated effects. Since this issue arises in essentially every “fetal origins” study, we suggest several ways in which future studies could both deal with selection as well as estimate the extent to which it explains the long-run impacts of early life shocks.

We hope our results will aid in the design of better prevention policies for mental health disorders in the developing world. We also show that certain groups are more susceptible to long-run mental health impacts, and thus should perhaps be targeted by policy interventions: impacts are largest for men, for farmers, and for the Akan, the biggest ethnic group in Ghana.

In sum, mental health disorders constitute a substantial problem across the developing world, with regard to population health as well as the economy. We show that in addition to ongoing efforts by governments to improve mental health care infrastructure, attention must be devoted to tackling the long-run causes of these disorders, particularly in vulnerable populations like agricultural commodity producers.

Achyuta Adhvaryu is an assistant professor of business economics and public policy at the University of Michigan’s Stephen M. Ross School of Business. His co-authors, James Fenske and Anant Nyshadham, are assistant professors of economics at the University of Oxford and the University of Southern California, respectively.