“the gentlest hand … modern economy, therefore, is the most effectual bridle ever was invented against the folly of despotism.” — Sir James Steuart (1767)

Hirschmann, in a classic of modern political economy (Exit, Voice and Loyalty, 1977), questions the effectiveness of this ‘gentlest hand’, and the traditional notion that despots will be reigned in by economic competition alone. What economists have been slow to embrace, he suggests, is the option of voice: being able to complain—and be heard—when things are broken. Historically, when considering government performance, it has not necessarily been easy to exercise voice, both due to a lack of anyone who will listen, and due to an inability to access and use the information to develop a voice.

Recent noisy uprisings in many countries and regions suggest that voice is a relevant consideration in economic and social change, and that voice is fostered by a range of modern technologies when these are made available. In this post I will look at the Open Data movement, discuss how this increases a people’s voice, and suggest why and how we must embrace this movement.

Open Data is Available

Like open source software, the idea behind Open Data is that this is information which belongs to all people, and which all people should be able to access, analyse, and use as they like. Governments are increasingly making data collected as part of their service delivery available in large online repositories where users can simply search for and download nationally relevant data. Although these initiatives started with governments in developed countries, this is now available in lower-income countries including India, Kenya, Chile, Uruguay and Morocco, among others. There has also been a push to take this Open Data and use it in ways which benefit social development. Initiatives which build on Open Data such as Code4Kenya and CodeandoXChile are piggybacking on the wave of newly available data to build user-friendly government budget interfaces, open school performance indicators, and provide health access information to citizens. These initiatives came about based on the availability of Open Data but are run and maintained principally by a public who responds to no governmental requirements or restrictions, and who speaks nearly entirely to other members of society.

Open Data has a role in defining how people and governments interact

User-friendly Open Data interfaces—such as those which can be linked with smart phones and publicly accessible computer terminals—can certainly provide citizens with a simplified way to search through complicated databases of public services availabilities and requirements. However, on top of simplifying search for public services, Open Data can act as an important check on State performance. Indicators such as public servant salaries, effectiveness of education providers, ability of law enforcement, and directions on how and where to vote have all been created using large Open Data bases which can be followed in real time by all citizens.

Open Data needs to be used

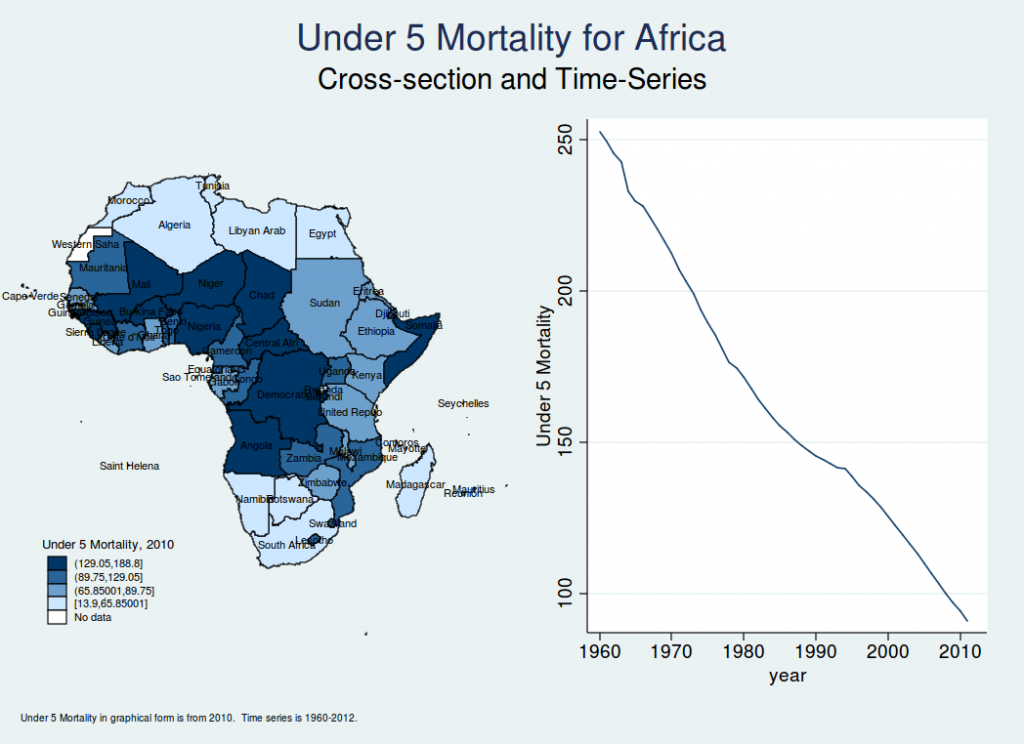

The challenge in Open Data then is in generating interfaces to make these large databases accessible. This is a two-part challenge: one part is simply facilitating the visualisation of data and the second part is in opening up access by increasing data-literacy. The first of these challenges, opening large databases and making them understandable in a simple way, is well under way. The World Bank hosts an enormous range of data (8,079 indicators to be exact) which can now be directly (and freely) accessed through programs such as R and Stata. Front-ends for these programs such as the worldstat Stata module I have made available online are also increasingly common (see figure 1).

The second part of the challenge, making citizens more data-literate, is perhaps the principal bottleneck in the Open Data movement. While it is certainly a good thing that a larger array of data is available to be communicated with the public, the limits of what is actually done with this freed data are set only by the degree that people are unsure of how to access and what to do with this. Where a larger group of citizens are actively accessing, exploring and communicating the results housed in Open Data repositories, society as a whole will be more engaged with the decisions governments make, and more importantly, how these map into social results. This suggests that digital education may be a worthwhile investment in school curricula – particularly for young girls and boys who truly are digital natives. The availability of massive open online courses, or MOOCs, is a start (such as free access to Harvard’s core computer science class via edX), but for countries to create educated citizens who can contribute to the democratic process (and as an added bonus to a dynamic labour market) teaching coding early would seem to be a worthwhile investment given recent trends in digital development and what we know about first mover advantage.

Open Data needs to be submitted

A burgeoning body of Open Data now exists. We can access information about what our governments spend, where they spend, and what the results of this investment look like. However, there is still much that can be done in this area. There is no need for Open Data to be restricted to national government databases. Economists and others who frequently collect and work with data can also submit their data via open repositories such as Google’s Public Data Explorer. What’s more, the marginal effort in uploading data to these interfaces where it can be used by all is minimal once collection has taken place. We should, wherever practical, begin to consider this as the typical way to communicate data, and barring serious concerns regarding privacy and sensitive information, should encourage national governments to follow the trend of opening up (de-identified) national datasets.

Hirschmann’s words then, as much as any other time, surely still ring true:

“Yet, in this age of protest, it has become quite apparent the dissatisfied … members of an organisation … can ‘kick up a fuss’ and thereby force improved quality or service upon delinquent management.”

We are, as ever, in an age of protest, and the voice society develops will grow louder and harder to refute when it is backed up with relevant data. This data—from independent international organisations and from national governments—is moving to become completely open. The only limit placed on its use is that on human ingenuity, and as long as citizens know where and how to look, this constraint will be insignificant.