Female genital mutilation (FGM) or female genital cut or female circumcision includes all procedures that alter or cause injure to the female genital organs. They are mainly carried out on young girls. FGM is recognized as an extreme form of discrimination and violence against women. Worldwide about 140 million girls and women are living with the consequences of FGM. The WHO estimates that in Africa more than 3 million girls are at risk for FGM annually (WHO, 2012).

Generating knowledge about the causes and consequences of FGM and planning effective policy interventions is a way to eliminate FGM. While there is a vast anthropological and ethnographical literature on the existence of FGM, economists have recently started to study this topic both from a theoretical point of view (Chesnokova and Vaithianathan, 2010; Coyne and Coyne, 2014) and empirically looking in particular at the determinants of FGM (Naguib, 2012; Ouedraogo and Koissy-Kpein, 2012; Molitor, 2014; Bellemare et al., 2015; Wagner, 2015) or at the effect of laws or program interventions against FGM (Camilotti, 2015).

Our recent CSAE working paper attempts to uncover women’s true attitudes towards FGM in Ethiopia, a country where about 74-80% of women are estimated to undergo the painful and unnecessary procedure even though it has been made illegal and is worldwide recognized as an extreme form of discrimination and violence.

The study uses survey data collected on 848 women in the Afar region during 2012 (Figure 1), including some women who had been targeted by a particular NGO intervention, designed to educate people on the harm caused by FGM. The intervention focuses on the dissemination of sexual and reproductive health knowledge and a change in traditional attitudes.

Figure 1: the Afar region in Ethiopia (Author’s photo – contact elisabetta.decao@phc.ox.ac.uk for license)

Figure 1: the Afar region in Ethiopia (Author’s photo – contact elisabetta.decao@phc.ox.ac.uk for license)

This research aimed to identify attitudes of women towards FGM. However, eliciting truthful answers when studying sensitive issues, such as attitudes towards FGM, is challenging. If asked directly, individuals may lie or refuse to answer, leading to misleading results. To account for this problem, this paper differs from the existing literature and uses an innovative survey technique called the “list experiment” to measure the attitudes. A list experiment is an indirect way of asking a sensitive question, so that the respondent may reveal a truthful response. The method presents respondents with a list of items and asks to indicate the total number of items with which they agree. The respondents are randomly divided in a control and treatment group. The control group respondents receive a list of non-sensitive items. The treatment group respondents receive the same list of non-sensitive items plus one sensitive item. The difference in the total number of items between control and treatment group identifies the proportion of people in the population that agrees with the sensitive item. In our survey, the control group was presented with the following list of statements:

- HIV can be transmitted through witchcraft or other supernatural means

- It is acceptable to use contraceptives to avoid pregnancy

- In a marriage both partners should decide on how many children they should have

For the treatment group, we added an extra item, concerning female circumcision:

- A girl should be circumcised

The contributions of this paper are three. First, it focuses on a new list experiment designed to measure attitudes regarding FGM in one of the areas where FGM prevalence is among the highest. Second, the most recent regression techniques developed to analyse the list experiment and the social desirability bias are used (Imai, 2011). This allows determining the existence and magnitude of systematic reporting measurement error of the true outcome. Third, the list experiment is used to study if respondents targeted by a NGO intervention are more or less likely to misreport their attitudes.

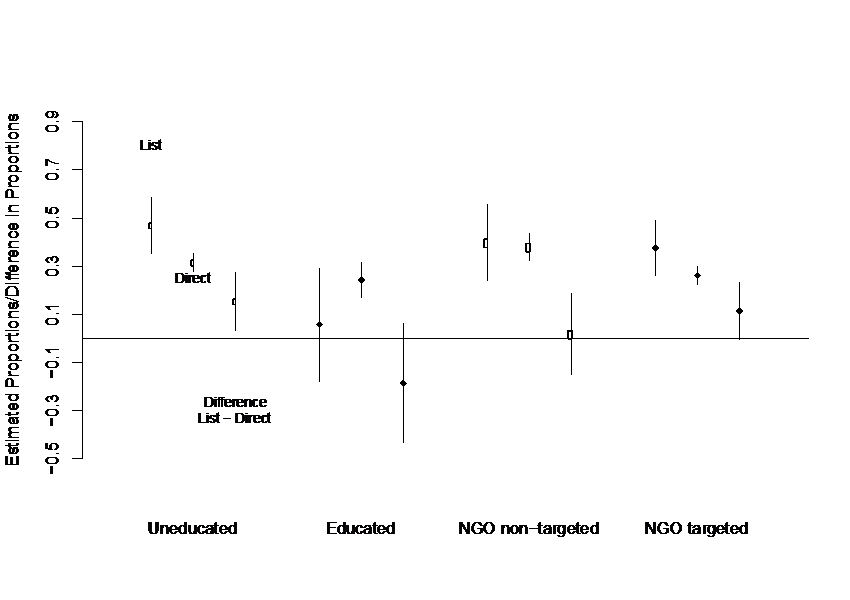

The main results are the following (see Figure 2). Firstly, the list experiment shows that educated women are less in favour of FGM (-41.2%, p-value=0.004) compared to the illiterate women. Secondly, when the results of the list experiment are compared with the results obtained with the direct question to test the social desirability bias, we find that uneducated respondents underreport their attitudes by 16% (p-value=0.013). This indicates that illiterate women seem to be less willing to share publicly their real attitudes concerning FGM support. The educational level may affect incentives in being cut. If being cut increases the chances to get a better husband (Chesnokova and Vaithianathan, 2010), we may argue that uneducated women have more to lose if they do not favour the practice, while educated women have better chances in the job market and depend less on marriage (Ouedraogo and Koissy-Kpein, 2012; Molitor, 2014). This can also be reflected by the never married women who underreport their support towards FGM by 27% (p- value=0.065).

Figure 2: Estimated proportions and difference in proportions between list experiment and direct question by education and by NGO targeted status.

Figure 2: Estimated proportions and difference in proportions between list experiment and direct question by education and by NGO targeted status.

Another interesting result concerns the NGO effect. By comparing the estimates obtained with the direct and indirect questioning, we find that women targeted by the NGO intervention underreport their support towards FGM when the list experiment is used to ask their opinion instead of the standard direct question (the difference is 12%, p-value=0.060). It is possible that the respondents in the NGO targeted areas conform to the expectations of those who provided the program treatment. The NGO campaign aims at changing the local FGM customs and this may increase the social pressure around FGM resulting in a stronger incentive to reveal a biased answer.

Is the NGO effect measured with the list experiment different enough from the one measured with the direct question that we can say with confidence that the NGO intervention may not have actually changed people’s attitudes, but rather how respondents report it (social desirability bias)? In this paper we can only estimate the underreporting due to social desirability bias. We cannot claim that the NGO intervention is not working in changing people’s attitudes and therefore behaviours. Our analysis is not an impact evaluation of the NGO program. To evaluate the intervention we would need to have pre- and post-intervention data on NGO targeted and not-targeted individuals. Then it would be possible to study if the NGO treatment effect is measured with error by comparing the answers to a standard survey question (direct question) with the ones obtained with a ‘validation’ survey question (e.g., list experiment) (Blattman et al., 2015). This would tell us if the conclusions about the impact of the program are affected by how the sensitive outcome is measured. Moreover, it would be even more useful to evaluate the intervention after a long period of time so that actual behaviour (e.g., cutting young girls) can be observed and compared with different measurements of attitudes. We leave this for future research.

Lack of empirical evidence on the support towards FGM, and most importantly lack of understanding of how biased direct questions can be, make our study the further step to a future line of research that aims at focusing more on how to measure sensitive outcomes. We believe this is especially important in the context of policy impact evaluations.

In conclusion, we suggest that both quantitative survey methods, such as list experiments, endorsement experiments or randomized responses, and qualitative survey methods, should be added to surveys, such as the Demographic and Health Survey for example, to measure if respondents misreport their attitudes or behaviours when the outcome of interest is sensitive. They could be applied to other stigmatized health topics, such as, for example, domestic violence or sexually transmitted infections.

The authors:

Elisabetta De Cao: University of Oxford, Centre for Health Service Economics & Organisation University of Oxford, United Kingdom. Corresponding author: elisabetta.decao@phc.ox.ac.uk

Clemens Lutz: University of Groningen Department of Innovation Management & Strategy University of Groningen, The Netherlands.

Funding source: NWO/WOTRO, grantnumber: W07.72.2011.115

References

Bellemare, M.F., Novak, L., Steinmetz, T.L., 2015. All in the family: Explaining the persistence of female genital cutting in West Africa. Journal of Development Economics 116, 252–265.

Blattman, C., Jamison, J.C., Koroknay-Palicz, T., Rodrigues, K., Sheridan, M., 2015. Measuring the measurement error: A method to qualitatively validate survey data. NBER Working Paper No. 21447.

Camilotti, G., 2015. Interventions to stop female genital cutting and the evolution to the custom: Evidence on age at cutting in Senegal. Journal of African Economies, 1–26.

Chesnokova, A.C., Vaithianathan, R., 2010. The economics oc female genital cutting. The B. E. Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy 10, 64.

Coyne, C.J., Coyne, R.L., 2014. The identity economics of female genital mutilation. The Journal of Developing Areas 48, 137–152.

Imai, K., 2011. Multivariate regression analysis for the item count technique. Journal of the American Statistical Association 106, 407–416.

Molitor, V., 2014. Family Economics in Developing Countries. Ph.D. thesis. Universita ̈t Mannheim.

Naguib, K., 2012. The effects of social interactions on female genital mutilation: Evidence from Egypt. Working Paper, Boston University.

Ouedraogo, S., Koissy-Kpein, S.A., 2012. An economic analysis of female genital mutilation: How the marriage market affects the household decision of excision. Unpublished Manuscript.

Wagner, N., 2015. Female genital cutting and long-term health consequences – Nationally representative estimates across 13 countries. Journal of Development Studies 51, 226–246.

WHO, 2012. Female Genital Mutilation, Fact Sheet 241. Technical Report. World Health Organization.