Mobile money services offer a new way to quickly and easily send money long distances. After starting in Kenya in 2007, they’ve grown dramatically over the last decade, with mobile money services now available in 93 countries with over 400mn users. 19 countries now have more mobile money accounts than bank accounts and mobile money account use has now overtaken PayPal in terms of active users. The number of services offered by mobile money providers has also been rapidly expanding, starting with transfers and progressing through savings accounts, insurance and payment in shops.

In Kenya, some positive effects of mobile money services have been found, with Jack and Suri (2014) showing the potential for mobile money services to facilitate consumption smoothing after rain and health shocks and Mbiti and Weil (2011) finding that mobile money services increase the frequency of remittances and change the pattern of rural urban transfers. My recent CSAE working paper adds to this growing literature by examining how mobile money services have affected risk sharing in Tanzania.

The introduction of mobile money services allow new and previously difficult to maintain risk sharing networks to form, for example between a migrant in the city and the family back home in a village. When risk sharing was confined to the village, households could only share risk against shocks which were uncorrelated across households, for example illness or loss of employment. They couldn’t insure against aggregate shocks affecting the entire village at once, for example droughts or floods.

Mobile money services make it possible for households to smooth consumption after aggregate shocks, by sharing risk with someone in a location far enough away that it’s not affected by the same shock at the same time. However, these new risk sharing relationships can undermine traditional village based risk sharing networks, to the potential detriment of non-mobile-money users.

My paper asks:

- Do mobile money services benefit users by allowing consumption smoothing after an aggregate rainfall shock?

- Are the benefits of mobile money services shared with other non-users in the village?

To answer these questions, I use three waves of panel date from the Tanzania National panel survey in a difference-in-difference specification. I define an aggregate shock both as a self-reported drought or flood and as a 1 standard deviation absolute deviation from mean rainfall.

Overcoming self-selection effects into mobile money use

Since I am using observational data for my analysis, there are two potential self-selection effects which could bias my results. The first of these is selection into mobile money use by the household, if selection depended on a variable that was time varying and unobservable. I control for this effect by:

- Focusing on the interaction of a rainfall shock with mobile money use

- Showing that households which experience more rainfall shocks aren’t more likely to use mobile money

A second source of potential bias is agent selection into villages. A mobile money agent is required to withdraw and add money to your mobile money account and it is possible agents select into the most profitable villages where consumption smoothing is also easier. I control for this by:

- Showing that having an agent in a village is not correlated with observable characteristics of the village or of households living in that village. This seems reasonable considering most agents are small shop owners who traditionally sold sim cards and are present in most villages.

- Conducting a placebo test on future mobile money use using two rounds of data before mobile money services were introduced and find no effect of future mobile money use on past consumption trends.

Main results

I find that households benefit from mobile money services when there is an aggregate shock but don’t share these benefits with their neighbours. Mobile money services help users of these services smooth household consumption after aggregate rainfall shocks, defined as a drought or flood. While an aggregate shock leads to a 5-10% fall in consumption per capita, households using mobile money services experience an increase in their consumption after an aggregate shock which balances this out. Mobile money services also lead to higher consumption of every household in the village (even those not using mobile money themselves) in periods when there isn’t an aggregate shock, resulting in average household being 10% higher than it would be with no mobile money users. However, when there is an aggregate shock, non-users of mobile money services don’t receive any help from users and so experience a drop in consumption. This is in a context where I cannot reject perfect risk sharing in response to idiosyncratic shocks.

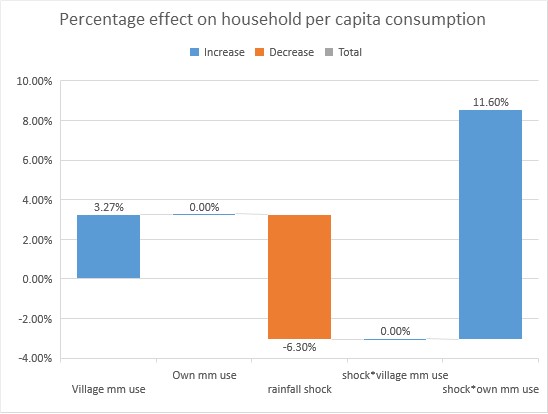

These results are illustrated in the following figure:

Per capital consumption is increase in the proportion of the village using mobile money services. At the mean of 1/3 of the village using these services, average village per capita consumption is 3% higher. Once village mobile money use has been accounted for, own mobile money use has no additional effect on per capita consumption. This changes after a rainfall shock, which causes a 6% fall in consumption. Now village mobile money use has no beneficial effect, while own mobile money use leads to a 12% increase in consumption, more than cancelling out the negative shock. This means the non-mobile-money-using neighbours of mobile money users still experience a 3% fall in their consumption on average, while mobile-money-using households have money to spare.

Implications for policy and research

These results raise the question of why the consumption of non-mobile-money-users in villages with other mobile-money-users is not smoothed after an aggregate shock, especially considering mobile money users appear to experience a gain in their consumption after the shock. This is an interesting area of future research, with potential alternative explanations being lack of norms related to sharing after an aggregate shock and changing risk sharing relationships. It would also be interesting to examine why certain households take-up mobile money services and others don’t. Is there a subsection of people who are unable to benefit from these services and how can we help overcome any barriers to their use? Examining this in more detail would give insight into who benefits from new financial services.