Households in traditional societies often deviate from the form of the nuclear family household that dominate in developed economies. Grandparents and grandchildren, married siblings, other extended family members, or even unrelated individuals may cohabit, produce and consume together.

In sub-Saharan Africa, there is evidence that the prevalence of nuclear family households is rising, in both urban and rural areas. It raises the question what is driving this change and what consequences it may have for the way households allocate resources.

The role of extended families and kinship networks in economic interactions has received considerable attention from economists in recent years (literature reviewed by Cox and Fafchamps 2008) but with a focus on extended family members who inhabit separate households. Whether and how the cohabitation of extended family members affects intra-household allocation is less well-understood.

Agricultural households in Burkina Faso provide an interesting setting for exploring the relation between household structure and decision-making because of the diversity of family ties that exists within the same household. The setting also has two distinctive features which make it easier to formulate and test hypotheses related to household production: (i) the practice of assigning farm plots, individually, to adult household members for which they control production choices, as well as the proceeds of farm output (Udry 1996) and (ii) besides these ‘private’ plots, the presence of ‘common’ plots which are farmed collectively under the management of the household head (Kazianga and Wahhaj 2013; Guirkinger and Platteau 2015).

Using data from a panel survey of agricultural households in Burkina Faso, conducted by the Ministry of Agriculture, we find, within the same geographic, economic and social environment, that nuclear-family households achieve near Pareto efficiency in allocating productive resources and Pareto efficient allocation of consumption, while extended-family households do not.

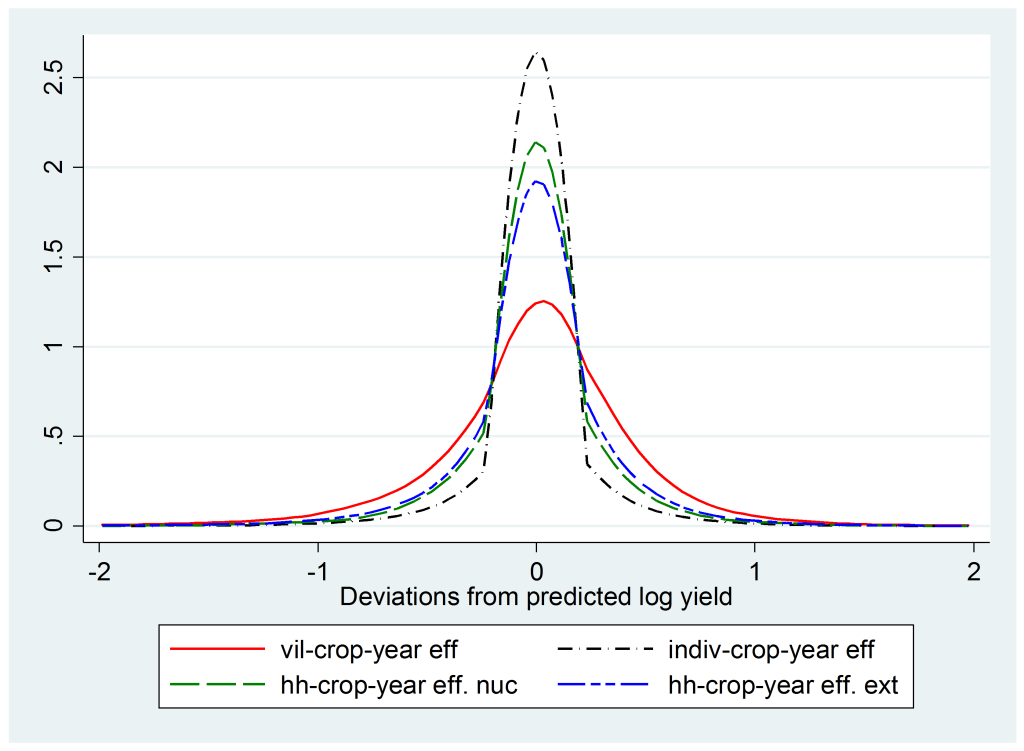

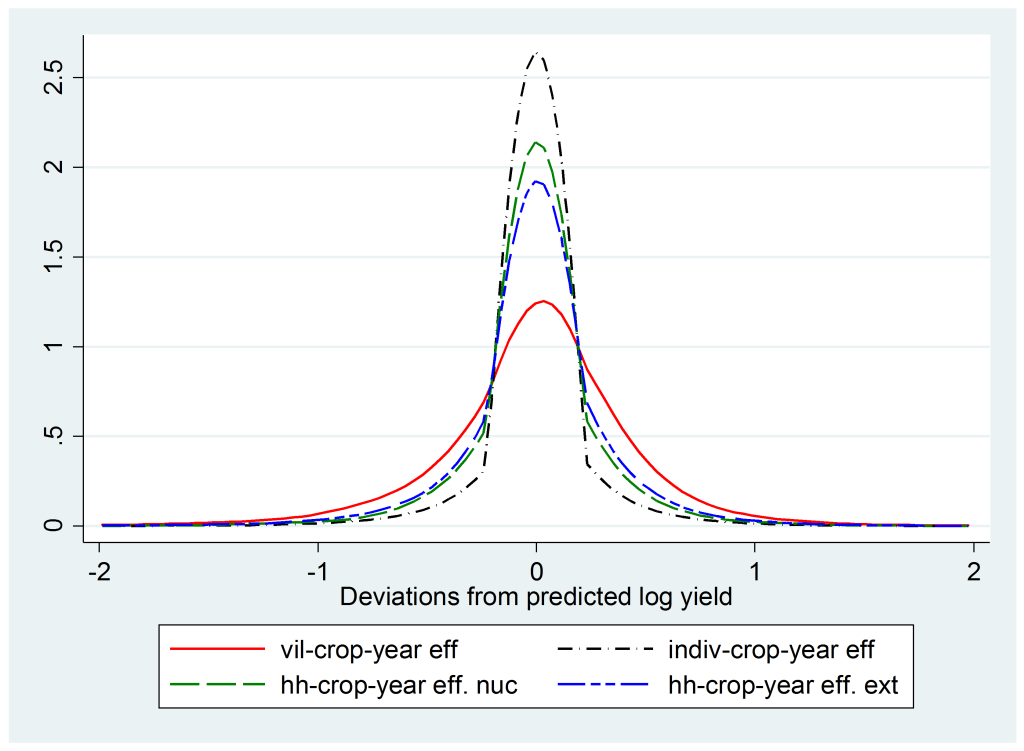

This pattern is captured in the following figure which shows the distribution of plot yields across farm plots planted to the same crop in the same year (i) belonging to the same nuclear-family household and (ii) belonging to the same extended-family household, after controlling for differences due to the physical characteristics of the plots. For comparison, the figure also shows corresponding distributions for farm plots (iii) within the same village and (iv) managed by the same individual.

For each group, the dispersion of yields captures the potential for improving output by reallocating resources, and therefore a wider dispersion implies greater inefficiency. The household-level distributions, for both subsamples, lie between the village-level and individual-level distributions. This is consistent with the findings by Udry (1996) and Kazianga and Wahhaj (2013) and implies that the household is more efficient than the village at allocating resources across farm plots that belong to the group, but not as efficient as the individual. We also see from the figure that there is greater variation in plot yields across apparently identical plots for extended family households as compared to nuclear family households. The equality of the two distributions is rejected at any conventional level using a Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, implying that the allocation of production resources is more efficient in nuclear family households than for extended family households.

We develop a theory where household members with closer familial ties exhibit higher levels of altruism towards each other (drawing on the evolutionary approach to altruism and familial ties, based on the work of Hamilton (1964)), which in turn motivate them to make intra-household transfers close to that required for efficiency. The theory predicts that household members who share a nuclear family tie (as opposed to an extended-family tie or no family ties) should contribute higher levels of labour on each other’s individually owned farm plots. This is confirmed by data on agricultural labour contributions by different household members on individually owned farm plots.

Using data on consumption expenditures by different household members, we implement two tests of intra-household risk-sharing, based data on consumption expenditures and idiosyncratic shocks to income from specific farm plots, and data on child anthropometrics and shocks to mothers’ farm income. With both approaches we are able to reject the hypothesis of efficient risk-sharing for extended family households but not for nuclear family households.

Farmer of cooperative UNPCB in village Kayao (Burkina Faso)

Farmers cultivating soil in village Fada (Burkina Faso)

We argue that the frequent presence of extended-family members and unrelated individuals within the household reflects a household’s response to the absence of markets for labour exchange and risk-sharing: the additional household members provide extra labour (in exchange for room and board and use of household land for farming) and serve as a means of income diversification. Consistent with this argument, we find that household heads with more inherited land and exposed to greater income volatility (due to local rainfall conditions and the characteristics of their inherited land) are more likely to end up with extended-family households.

The two theories of intra-household allocation that have received the most attention in the academic literature and tested most frequently using household data are the Unitary Model and the Collective Model. The Unitary Model, which postulates that the household behaves as if it were a single individual, has been consistently rejected by empirical evidence. On the other hand, tests of the Collective Model, which postulates that household members with conflicting preferences are able to achieve Pareto efficient outcomes, has yielded mixed results — not rejected for labour supply decisions in developed countries or consumption decisions in developing countries, but commonly rejected for production in African households. Our findings regarding the allocation of resources within nuclear and extended-family households provides a way of reconciling these two strands of empirical evidence in the literature that have either failed to reject or have rejected Pareto efficient allocation of household resources.

The wider implication of our analysis is that as markets develop and agricultural land scarcity increases, extended-family households should give way to nuclear family households. This should result in more efficient allocation of resources for production and consumption because of the ties that bind together members of the nuclear family.

Link to the CSAE Working Paper

Harounan Kazianga is an Associate Professor of Economics at Oklahoma State University. His research focuses on rural economic activity in Sub-Saharan Africa. He has conducted extensive research in Africa on technological change in agriculture, the use of financial markets, asset accumulation and gift exchange to cope with risk, gender relations and the structure of household economies, education and a variety of other aspects of rural economic organization.

Zaki Wahhaj is Senior Lecturer in Economics at the University of Kent. His research deals, broadly, with themes of social norms and household decision-making in developing countries, including the role of social norms in intra-household resource allocation and household formation, issues relating to female education and economic participation, and interactions between formal law and customary practices. His current research is based in South Asia and West Africa.