Last year, while wandering around a slum in Dar es Salaam with a colleague, I happened upon a local landowner who was visibly displeased with how his plot had been demarcated in a recent large-scale land survey. A few years prior, after returning from a ten day trip, he discovered that someone had purchased the patch of land adjacent to his house which he had been using for growing vegetables. In its place: a new house, already built during his absence. What was particularly astonishing about the dispute was the fact that the man’s long-standing neighbours, with whom he admittedly had a poor relationship, had supported the sale while he was away.

We often think of property rights as being objectively verifiable – if you own something there must be a receipt or a government record somewhere proving your ownership. If you decided to sell your house tomorrow, neither the real estate agent nor any potential buyers are going to rely on your neighbour’s perceptions of your ownership as a basis for the sale: they are going to want to see a government-approved title deed. It is with substantial faith in this formal system of property rights that I could go on my own ten day holiday earlier this month without fear that someone would invade my back garden in the meantime (even if my neighbours did go along with it).

Until relatively recently, most people living in the unplanned settlements of Dar didn’t have access to this kind of formal tenure, so most property rights were characterized by informal forms of tenure. Informal tenure is a bit of a catch-all term, ranging from customary forms of tenure, which rely on established practices and, well, customs to determine ownership, to quasi-legal forms, where households write up their own transfer agreements and have them certified by a local court. Ultimately, much of informal tenure in these settings is determined by one’s relationship with the community: you own the land because the people around you agree that you own the land.

One particular reason why neighbours might be more likely to support each other as well as cooperate and coordinate in enforcing each other’s ownership rights is if they come from the same ethnic background. There’s a large literature documenting how co-ethnics are more likely to trust one another, have a distinct advantage in cooperation, and are often more adept at producing public goods . While some research has suggested that Tanzania is less susceptible to these co-ethnic biases, there is still good evidence that ethnicity and tribal norms matter in the decisions that people make. For example, respondents in the 2001 and 2005 waves of the Afrobarometer survey were significantly more likely to say they trusted member of their tribe than members of other tribes.

So what happens when you have an extremely ethnically-diverse setting like Dar es Salaam, where informal tenure is the norm, and suddenly formal tenure becomes an option? In 2005, many households living in the city’s slums were suddenly given the option to buy a limited form of land tenure, a 2-5 year renewable lease on their land known as a residential license. Roughly 40% of landowners in the slums did so, leaving a sizeable share of people who did not opt for what was a fairly cheap (approximately $6, not counting future land taxes) way of formalizing their land.

While it is easy to see why households who have little faith in their own informal tenure security might be quick to buy a land title, what about households who are surrounded by those of the same ethno-linguistic background, who might otherwise feel fairly secure? If a given household’s sense of informal tenure, bolstered by the presence of co-ethnics living nearby, is strong enough, will they be less likely to buy a formal land title offered by the government?

I investigate precisely this question in a new CSAE working paper. Using a unique census of two large adjacent slums in Dar es Salaam, I investigated whether households with a greater percentage of coethnic neighbours (those from the same ethnolinguistic background) were less likely to buy a residential license from the government.

Simple correlations suggest that this is the case: households with a larger percentage of coethnics living nearby were significantly less likely to have bought a short-term land title. Yet it isn’t entirely clear that this is a causal relationship: for example, the kind of people who choose to live near those of the same ethnic background might have different beliefs over the effectiveness of formal land tenure, or reside on lower-quality land for which the returns to titling are quite low.

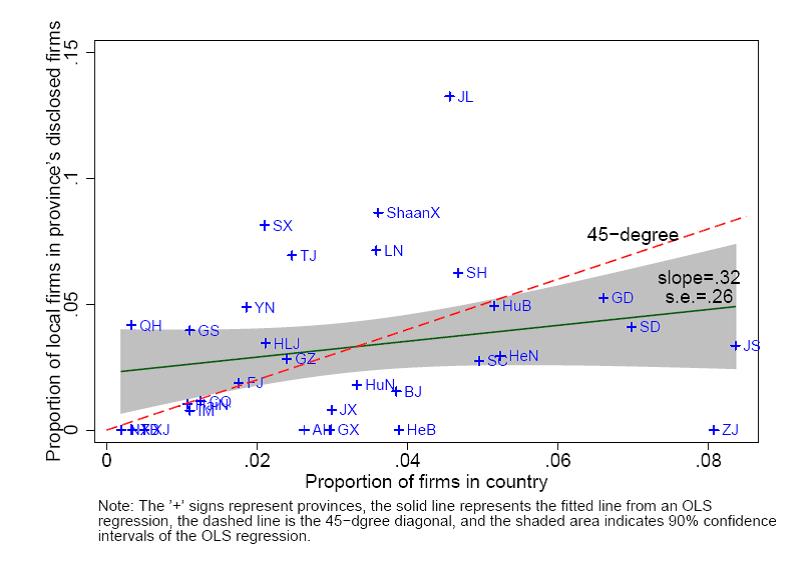

While controlling for a host of household, plot, ethnic and geographic characteristics might reduce these concerns somewhat (and this is all done in the paper), the main issue here is still sorting: certain types of households may choose to live near coethnics. To get around this, I rely on the fact that households who move to a slum have very little control over who moves in after them, so while households may choose where they want to live, they can’t easily choose who moves in next. Thus, relying exclusively on changes in the ethnic composition of nearby households which occur after a household moved into the slum should allay concerns that the main result is being driven by certain types of households.

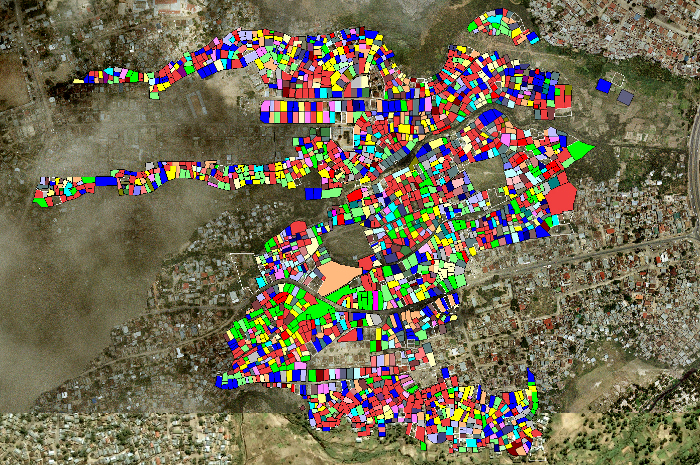

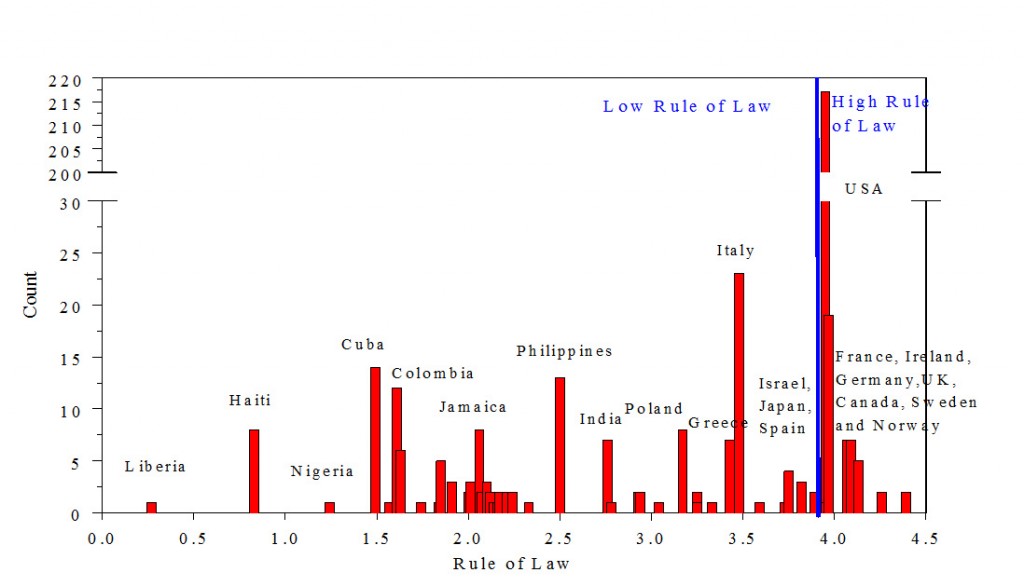

The main results are robust to both this new approach and several different definitions of `coethnic’. In the end, if appears that households living near others of the same ethnic background have observably lower demand for land titles. These effects are, in theory, quite large – households who are completely surrounded by coethnics should be nearly 60% less likely to buy a land title than those who are completely isolated. However, in practice, slums like those in Dar es Salaam are so diverse (see the image at the top of this blog post) that these extremes are rarely realized in practice.

This might actually one of the chief benefits of urbanisation: if Dar es Salaam were more ethnically segregated and dominated by tribal enclaves, then these results suggest that the residential license roll-out would have even been less successful than it was. The absolutely astounding level of (integrated) ethnic diversity seen in the city might be what gives the Tanzanian government a partial advantage in providing property rights, by isolating households from others from the same tribe and forcing them to rely on the state to enforce tenure.

What is the main takeaway from this paper? Not only does ethnicity seem to still be an important factor in the decisions of ordinary Tanzanians, but it appears strong enough to influence the adoption of formal property rights, seen by many as one of the prerequisites to building a modern economy. It also reinforces the importance of informal notions of tenure in these settings, which might compete with, rather than complement, attempts to introduce formal tenure. Finally, while most work on the effect of ethnic heterogeneity on economic outcomes rely on country or regional-level analysis, more could be done to examine how ethnicity affects decisions at the household level.

You can read more here, where I also cover the potential mechanisms driving the result, and go into a bit more detail on what the implications are.