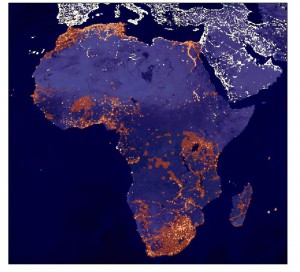

Sub-Saharan Africa has the lowest levels of infrastructure quality in the world. However, 80% of adults in Kenya, Ghana, Nigeria, and Senegal have a mobile phone, despite the fact that a large proportion of them live in poverty with no access to electricity. As shown in figure 1.a and 1.b, mobile phone subscriptions in sub-Saharan Africa have increased dramatically over the past decade, jumping from 15 million in 2000 to 650 million in 2012.

Figure 1: GSM Coverage in 1999 and 2008 (GSM Association, taken from Isaac Mbiti’s slides).

Discussing the opportunities brought about by the spread of this new technology was precisely the objective of the panellists for the first keynote address at the 2014 CSAE conference. For this very interesting session, William Jack (Georgetown University) Ignacio Mas-Ribo (University of Oxford Tufts University) and Isaac Mbiti (Southern Methodist University) were chaired by Simon Quinn (who, ironically, seemed more at ease with computers than the three IT specialists).

The speakers identified four main mechanisms through which mobile phones can provide benefits to their users in Sub-Saharan Africa (see below for a list of references).

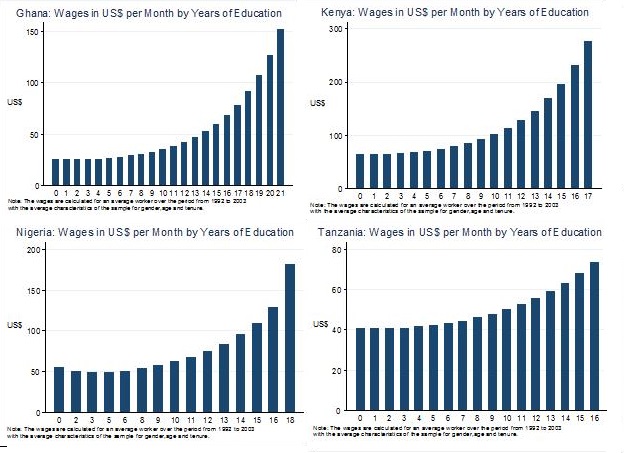

First, mobile phones create new business and job opportunities through improved communication and increased access to information. In remote rural areas, farmers are now able to instantaneously learn crop prices in a distant city market without having to pay otherwise unaffordable transport costs. This may in turn increase their bargaining power against intermediaries and stabilize their revenue (provided that the intermediary is not monopolist). Similarly, thanks to mobile phones, day labourers are now able to call peers who live in cities to find out about job opportunities.

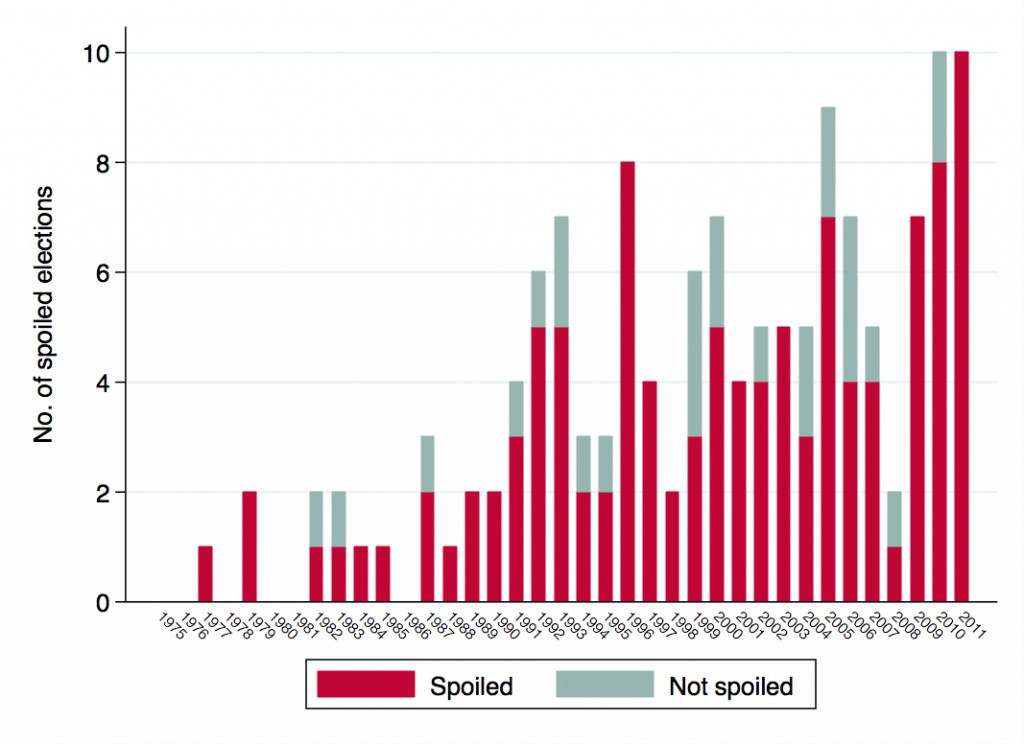

Second, mobile phones provide a very practical platform for improving governance and democracy. In India for example, mobile phones have been successfully used to facilitate the reporting of cases of corruption. In Burundi, Kenya, Mozambique and Nigeria, citizen-based monitoring schemes were put in place in order to report cases of electoral fraud and violence. In a similar way, mobile phones have been used to facilitate election monitoring and increase electoral turnout.

Third, the mobile phone technology improves the quality and the outreach of development programmes related to health, education and emergency response. In high-prevalence countries, people living with HIV can now receive text messages daily, reminding them to take their antiretroviral medication. Mobile phones have also been used all around Africa for monitoring and tracking epidemics outbreaks, for supporting diagnosis and treatment by health workers and for sending health education messages.

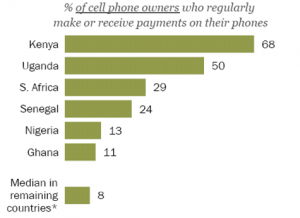

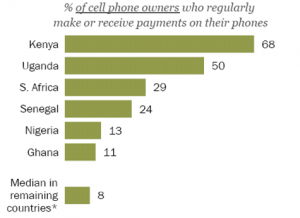

Finally, and this was the most important part of this keynote address, mobile phones can improve informal insurance mechanisms and facilitate access to modern banking services via the development of mobile money accounts. Mobile money accounts usually involve a set of applications facilitating financial transactions via mobile phone, including paying bills and transferring money and airtime between individuals. As underlined by Isaac Mbiti, there are now more registered mobile money accounts than bank accounts in Cameroon, DRC, Gabon, Kenya, Madagascar, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia and Zimbabwe, thereby demonstrating the attractiveness of this service.

Figure 2: % of cell phone owners who regularly make or receive payments on their phones

The mobile money programme that has received the most attention in the literature (and during this session) is the programme M-Pesa which was launched in 2007 in Kenya. As of September 2009, M-Pesa had 8 million subscribers, with almost 40 percent of Kenyans having ever used the service to send or receive money.

As shown by William Jack, the M-PESA programme allows its users to smooth consumption across income shocks, suggesting that M-PESA reinforces considerably informal insurance mechanisms. In line with this, William Jack showed that remittance networks are larger thanks to M-PESA. Thanks to the programme, remittances are more numerous, larger and travelling further. As show by Isaac Mbiti, money accounts not only improved informal insurance mechanisms directly, they also reduced the cost of remittances in general. Since the introduction of M-Pesa in Kenya, fees charged for domestic transfers by Western Union and MoneyGram fell by about 50%; pressure from M-Pesa accounts for about 60% of this drop.

Of course, the expansion of mobile money did not occur without any difficulties, and the highly-publicized success of M-Pesa is still suffering from replication troubles. As explained by Ignacio Mas-Ribo, since the benefit of joining a network is directly proportional to the number of people already on it, the set-up of mobile money services may be quite complicated. Mobile money therefore needs to reach a critical mass of customers in order to be viable and profitable. Furthermore, current mobile money systems suffer from their limited capacity of storage of value and their limited integration. There remains the question of whether these difficulties should be solved by increased competition or by public action (or both)…

Aker, Jenny C., and Isaac M. Mbiti. 2010. “Mobile Phones and Economic Development in Africa.” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 24(3): 207-32.

Dermish, Ahmed and Kneiding, Christoph and Leishman, Paul and Mas, Ignacio, Branchless and Mobile Banking Solutions for the Poor: A Survey (January 23, 2011). Innovations, Vol. 6, No. 4, Fall 2011.

Jack, William, and Adam Ray, and Tavneet Suri (2013). Transaction networks: Evidence from mobile money in Kenya. American Economic Review: Papers and Proceedings. 103(3): 1–8

Jack, W., & Suri, T. (2014). Risk Sharing and Transactions Costs: Evidence from Kenya’s Mobile Money Revolution. The American Economic Review, 104(1), 183-223.

Mas, Ignacio and Radcliffe, Daniel, Scaling Mobile Money (May 31, 2011). Journal of Payments Strategy & Systems, Vol. 5, No. 3, September 2011.

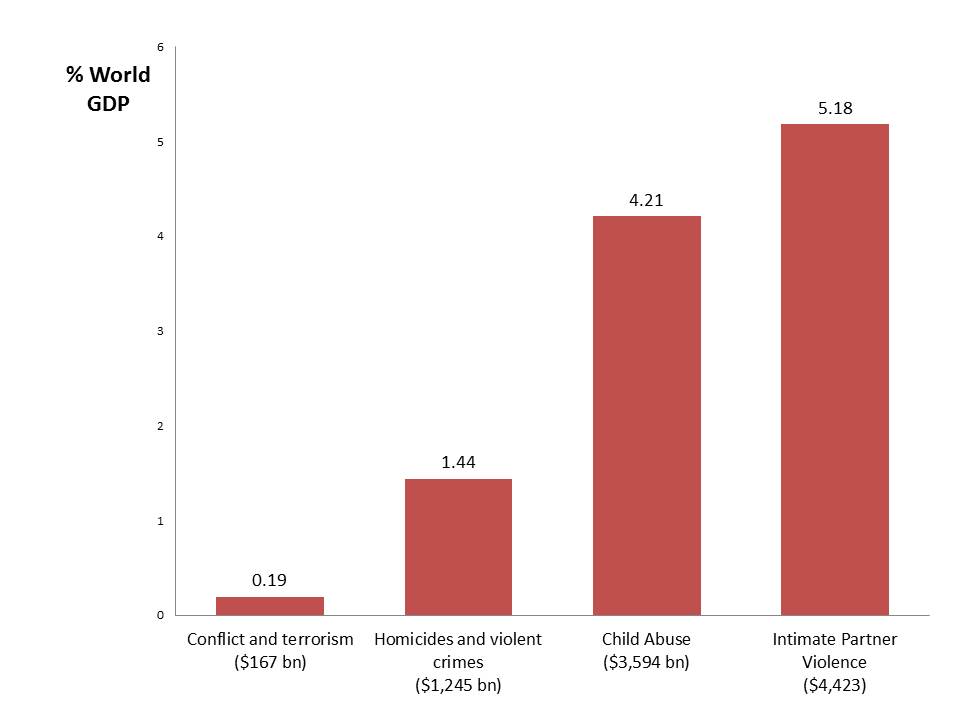

Figure 1 – The global cost of violence

Figure 1 – The global cost of violence