This blog post is based on a keynote speech given by Daniel Clarke at the 8th International Microinsurance Conference, on 8 November 2012.

Since 2003 there have been a large number of agricultural insurance pilots in low income countries. Many of these were weather indexed insurance pilots, where the claim payment to policyholders depended only on the weather (rainfall, temperature, etc.) at a nearby weather station. However, with the notable exception of the Indian Weather Based Crop Insurance Scheme which now covers over 11 million farmers per year, very few of these pilot programs have scaled up. Why is this and, more broadly, what are the lessons from all these pilots? This blog post outlines six lessons, and makes tentative suggestions for index insurance product design.

Lesson 1. Agricultural insurance is not a complete solution to agricultural risk (World Bank, 2011)

Agriculture is an uncertain business. Costs mean that formal sector insurance makes most sense for extreme, low probability shocks; risk retention through savings or credit, or risk sharing with friends and family can be more cost effective for less extreme, more frequent shocks. Moreover, investments in risk mitigation (e.g. irrigation or flood resistant seeds) are often more cost effective than insurance for fairly frequent events.

Lesson 2. Public sector roles are critical for sustainable scale-up (Mahul and Stutley, 2010)

Many pilots have mainly focused on the private sector role in market for agricultural insurance. However, successfully scaled-up agricultural insurance programs have typically been public-private partnerships. Government intervention can be motivated by market imperfections (e.g. index definition and data collection is effectively a natural monopoly in low income countries) or government pro-poor objectives (e.g. agricultural insurance as a market mechanism used to target social objectives).

Lesson 3. Farmers want reliable protection (Clarke 2011a)

Insurance is only attractive if you believe that the insurer will pay when you need it. For traditional indemnity insurance, insurers know from experience that takeup will be low if there is low trust in the insurance provider or there are too many important exclusions. Doherty and Schlesinger (1990) famously showed that this dislike of contractual nonperformance risk is rational. For indexed insurance, basis risk, the risk that the claim payment does not match the farmers’ loss, provides another reason why the insurance might not pay when it is most needed. For example, a farmer may lose his or her entire crop due to disease but not receive a claim payment from a weather indexed insurance policy because the weather at the contractual weather station was good. Basis risk can therefore supress demand, just as other forms of contractual nonperformance can. How much it will supress rational demand depends on the degree of basis risk.

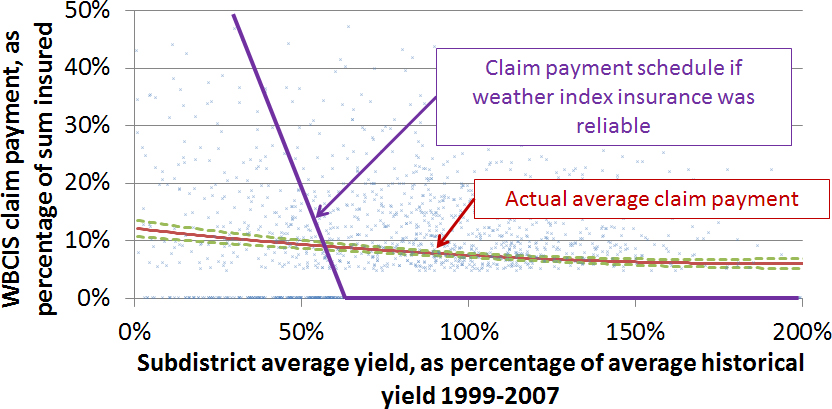

Lesson 4. Weather index insurance does not (seem to) offer reliable protection for farmers (Clarke et al. 2012)

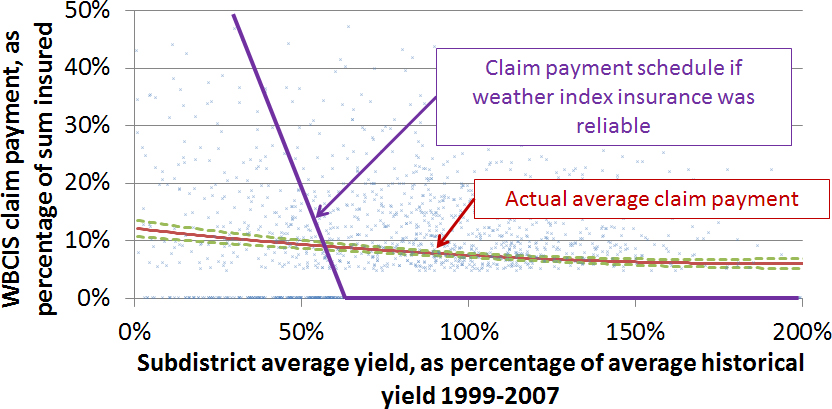

There is currently no convincing statistical evidence from any program suggesting that weather index insurance can be relied on to pay in years that are bad for smallholder farmers. Whilst statistical analysis of basis risk has not been conducted for most pilot weather index insurance programs, available evidence is very negative. For example, see the figure for a recent analysis of 9 years of matched weather and yield data for 318 weather index insurance products sold across one Indian state under the WBCIS from Clarke et al. (2012). The results of this analysis suggest that if yields are twice the long-run average the weather products will pay 6 percent of the sum insured on average whereas if yields are zero the weather products will pay 12 percent of the sum insured on average. The correlation between area average yields and indexed claim payments is only -13%. Whilst the yield data is unlikely to be perfect, this is quite a lot lower than we were expecting to find.

This may seem strange. Weather is clearly important for agriculture, so why is the correlation here so low? I would suggest three reasons. First, other perils such as pest, disease, wind, flood, frost, hail, and localised weather can cause catastrophic losses but are typically not well captured by weather indices. Second, farmer behaviour (e.g. planting date) is typically very difficult to capture in a formula set at the beginning of the season, and this may mean that the weather index insurance contract is particularly sensitive to rainfall over the wrong periods. Finally, the places in which weather indices have the most convincing rationale are the places with very poor historical yield data. However, without 30+ years of high quality production data, model calibration is likely to be poor.

Lesson 5. We need better claim payment rules, and mutuality may be a missing link (Clarke 2011b)

Weather index insurance proponents typically separate shocks into two categories: those caused by weather and those not. I would suggest that a different categorisation might be more helpful, namely splitting large shocks that affect a farmer into shocks that are large, on average, locally (systematic shocks) and those which only affect a small number of farmers (idiosyncratic shocks). These two kinds of shocks should be addressed differently.

- Idiosyncratic shocks: The formal sector cannot offer affordable protection for idiosyncratic shocks (individual indemnity insurance suffers from very high moral hazard and high costs), but communities may be able to offer protection against large idiosyncratic shocks through farmer groups, cooperatives, mutuals, etc.

- Systematic shocks: The formal sector can and should offer reliable protection for large systematic shocks. Weather or satellite index insurance does not seem to adequately capture aggregate shocks, but area yield (e.g. the Indian modified NAIS) or group multiple peril crop insurance (e.g. Mexican Fondos) may be able to.

Lesson 6. Meso-insurance for lenders has potential (Skees et al. 2007)

By taking agricultural risk away from the balance sheet of lenders, meso-level agricultural insurance could allow lenders to increase their exposure to the agricultural sector without being too exposed to large agricultural shocks. In turn this could support farmer investments in agricultural productivity (fertiliser, improved seeds).

What does this mean for smallholder farmer index insurance product design?

- Don’t believe stories, believe data. Regulators, donors and governments should demand that statistical analysis like that presented in the above figure be presented before any set of index insurance products are offered to people on low incomes. Insurance for the vulnerable should be safe. My guess is that most weather or satellite-based agricultural index insurance programs for smallholder farmers are currently not.

- Offer reliable products, and innovate behind the scenes. Area yield and area revenue indices are attractive in that they are designed to accurately capture aggregate shocks. However, it is not a question of yield data or weather data or satellite data; all can be useful. For example, the Government of India is piloting a modified National Agricultural Insurance Scheme (mNAIS), where the main claim payments to farmers are based on area yield indices but satellite data is used to target and audit crop cutting experiments and weather data may be used for early part-payments. They are also making innovative use of technology in speeding up and increasing the reliability of crop cutting experiment data (video recording crop cutting experiments with GPS-enabled cell phones, sending data to the insurers in real time, etc). In countries where audited, manipulation-free crop cutting experiments are not feasible for political economy reasons agricultural insurance for smallholder farmers may not be able to increase welfare.

References:

Clarke, D.J., “A Theory of Rational Demand for Index Insurance,” Department of Economics Discussion Paper Series 572, University of Oxford 2011a.

Clarke, D.J.,, “Reinsuring the Poor: Group Microinsurance Design and Costly State Verification,” Department of Economics Discussion Paper Series 573, University of Oxford 2011b.

Clarke, D.J., K.N. Mahul O. Rao, and N. Verma, “Weather Based Crop Insurance in India,” World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 5985, 2012.

Mahul, O. and C.J. Stutley, Government Support to Agricultural Insurance: Challenges and Options for Developing Countries, World Bank Publications, 2010.

Skees, J.R., J. Hartell, and A.G. Murphy “Using index-based risk transfer products to facilitate micro lending in Peru and Vietnam,” American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 2007, 89 (5), 1255–1261.

World Bank, “Weather index insurance for agriculture: Guidance for Development Practitioners,” Agriculture and Rural Development Discussion Paper 50, 2011.